The Oppenheimer Dilemma:

Navigating Science, Ethics, and Power in the Shadows of the Atom Bomb

Extended Thoughts from Dr. M.J. Soileau, Scientist in Residence

This summer, Christopher Nolan's film Oppenheimer took the country by storm. If you haven't seen it yet, I highly recommend that you do. Not only is Nolan a powerful storyteller, but the film is factual and compelling - and a good reminder to us all of the danger posed by the pulverization of nuclear weapons in arsenals around the world. Focusing on the evergreen issue of the moral qualms of scientists developing weapons of war, Oppenheimer poses a poignant question: do scientists have a moral obligation to engage in policy discussions beyond the technical details of weapons?

Morality! A topic too big for me to properly address in so few words. However, I shall do my best.

Many of the key scientists on the Manhattan Project (and the related efforts in England) were European immigrants who had fled Fascist powers in Europe, e.g. Germany and Italy. These immigrants were vocal proponents of the compelling argument for the development of America's atom bomb (or A-bomb).

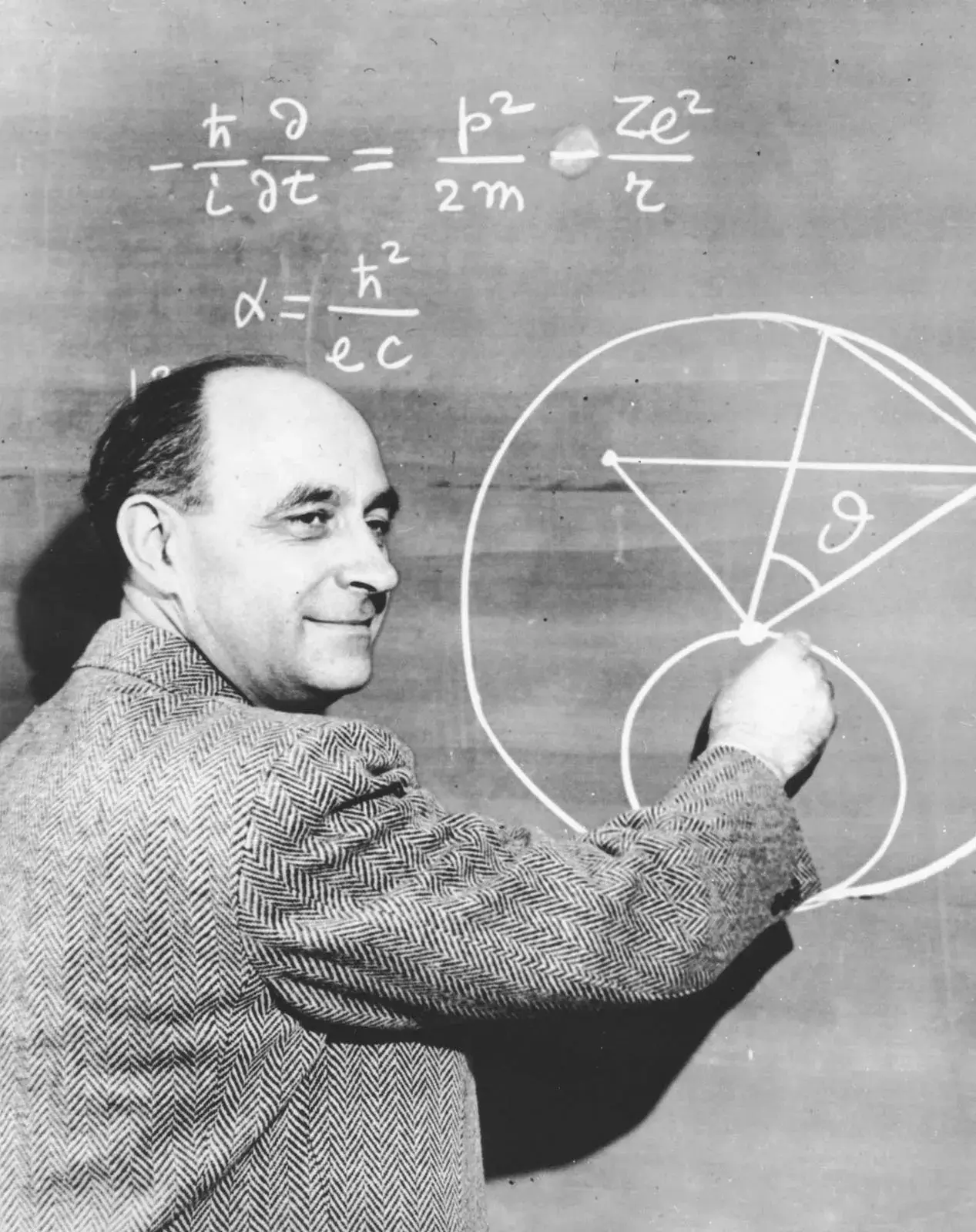

Enrico Fermi was one such scientist. He received his Nobel Prize in 1938 – the same year he fled Fascist Italy for the United States to join the Uranium Project at the University of Chicago. He joined other émigrés on this project, including Leo Szilard and Eugene Wigner, and the team developed the first sustainable nuclear reaction. That effort was initially meant to look at atomic fission as a source of energy. Fermi tried and failed to interest the US military in this possible energy source. He and his colleagues were aware of the possibility of a uranium bomb, but they doubted that such a bomb could be built.

Nazi Germany did not have such doubts. In 1938, German scientists split the atom. Then the German government embargoed uranium and moved the nuclear effort behind a wall of secrecy. These actions sounded the alarm with refugee physicists working with uranium. They correctly concluded that the Nazis were working on an A-bomb! Having experienced Nazi tyranny firsthand, they knew that Hitler would use such a weapon to ensure Nazi dominance of the world.

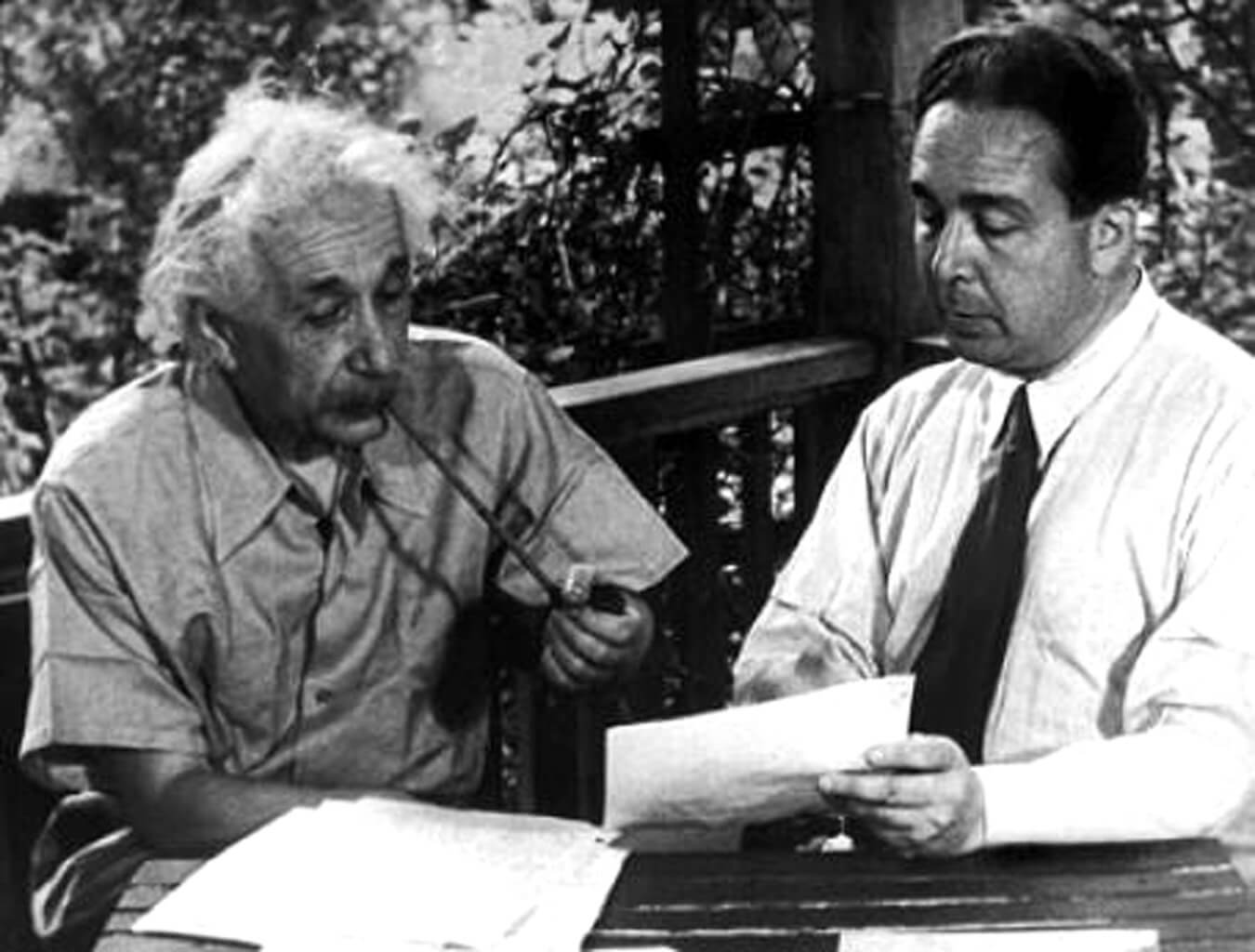

Hungarian émigré physicists Leo Szilard and Eugene Winger regarded it a moral imperative to alert US officials of the possibility of a German A-bomb (though it wasn’t yet known by that name). They sought the help of the world’s most famous scientist, Albert Einstein, to write a letter to President Roosevelt urging quick and rigorous action towards creating a weapon that would stand up to a German A-bomb. Einstein, an avid pacifist, had met the President. In fact, he’d been an overnight guest in the White House.

Together, Szilard, Wigner and Einstein drafted a letter that was hand-delivered to the President on October 11, 1939. This letter persuaded President Roosevelt to take decisive action towards creating the Manhattan Project. This was major policy advocacy by scientists, and it had a huge impact on the outcome of the war. Roosevelt set up a high-level committee (which included Ernest Lawrence and Vannevar Bush) to explore the feasibility of the bomb. Lawrence and Bush presented findings to the President on October 9, 1941 that an A-bomb could be built. Roosevelt gave the tentative go-ahead on January 19, 1942.

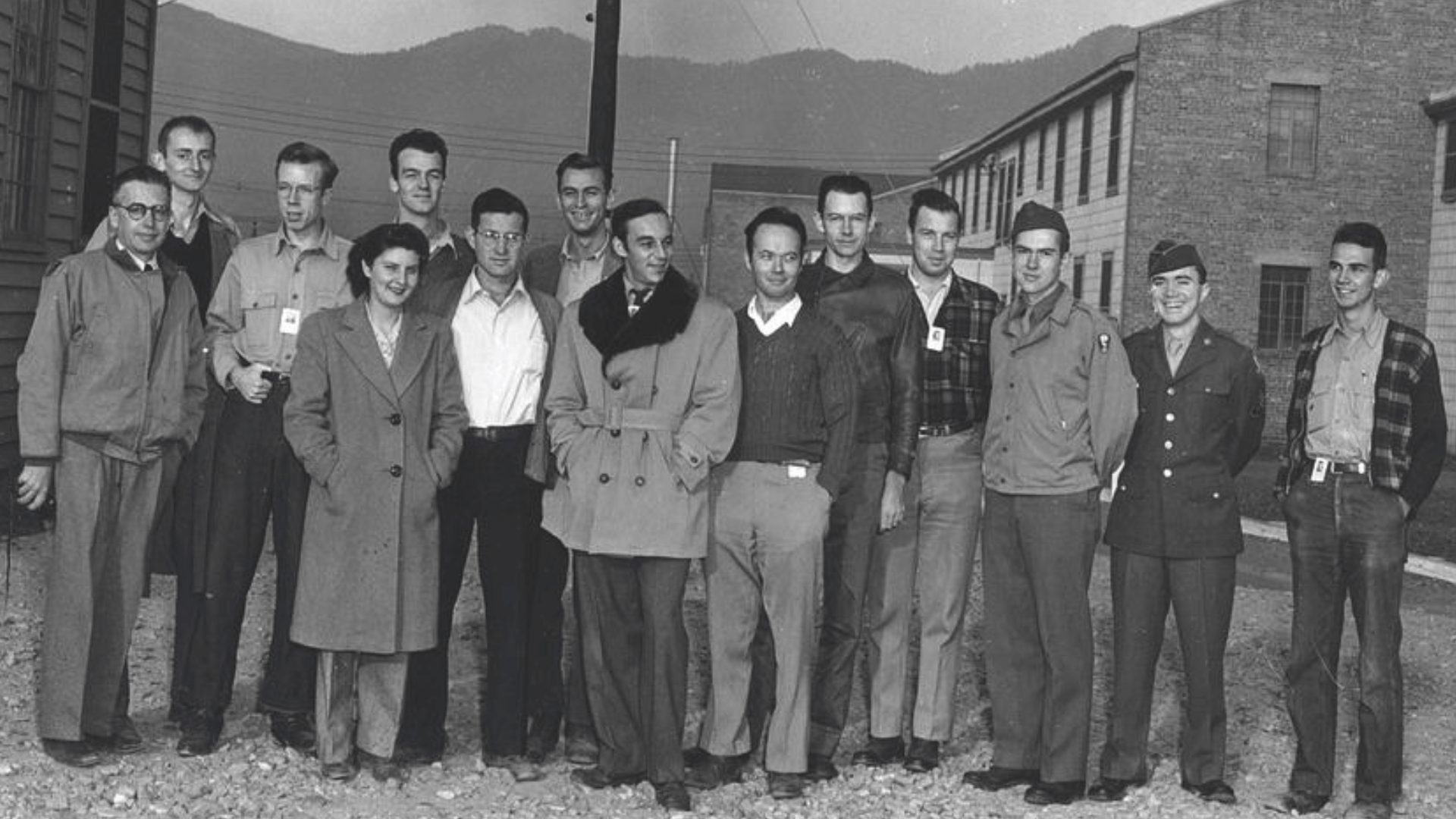

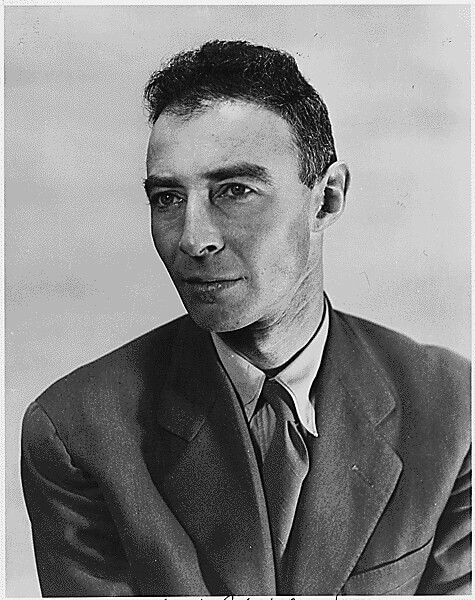

General Groves, appointed to lead the effort in June 1942, hired J. Robert Oppenheimer to lead the bomb's development. Among Oppenheimer's first actions was to recruit an international team of "science celebrities" for the project. This included 36 Nobel Prize winners (some of whom received the prize after the war).

Without question, Oppenheimer was the leader of the Manhattan Project, which developed the A-bombs that the United States would drop on Japan. Without question, this action was the ultimate defeat of the Axis powers, bringing an end to World War II (WWII). Without question, Oppenheimer had a deep understanding of the destructive power of A-bombs and the horrific consequences of a hydrogen bomb (or H-bomb) arms race.

Nolan's film ends with the portrayal of Oppenheimer's struggle with his conscience. In my view, his struggle was not about guilt for having led the development of the A-bomb but for what might come next.

At the war's end, Oppenheimer was a superhero to the American people. He and many others who developed the weapon were particularly suited to give input regarding the developing arms race and the H-bomb superweapons, and he took a stance, definitively arguing against further development of superweapons.

Many citizens - including many scientists - believed that this kind of advocacy should not be the role of the scientist. Oppenheimer's policy opponents viewed him as such a threat that they found it necessary to destroy him personally to discredit his opposition to the development of the H-bomb and his advocacy for arms control.

Years after the end of WWII, declassified testimony indicated that the FBI had files listing Oppenheimer, Leo Szilard, Enrico Fermi, and other scientists (particularly "foreign-born" scientists) as uncertain allies. But without such men, the Manhattan Project would not have succeeded.

We must understand that there was a moral imperative among the Allies to defeat the Axis powers in WWII. All aspects of society were mobilized for this cause, including the scientific community. Nolan's film hinted at this but did not fully develop the concept of the massive mobilization of scientific and engineering talent and industrial resources for the effort.

I encourage everyone to see the film and study the historical context surrounding the decisions made to help contemplate the world's next steps in nuclear armament. I pose the question to you: Should scientists advocate for policy regarding the science they develop?